Most informed coaches appreciate the importance of acceleration for field and court sports. It’s the most prominent type of speed in these sports and is a highly trainable part of the speed spectrum. However, with this importance and emphasis I’m seeing more programs and athletes that have overshot the acceleration emphasis into unbalanced programs that lack complementary running. The results of the acceleration imbalance are often physical restrictions and at times injuries from myopic short only programs.

Acceleration Overdose

Short acceleration training like 10s, 15s, 20s, hills, and sleds are very popular and, if done well, very effective options to train acceleration. However, if this is the only sprint and run training present the athlete tends to present with some of the following problems.

- 1.Restricted Hip Extension and Separation– Hip extension in acceleration is relatively more through the axis of the body than behind it. Thus, the elastic restraints of the hip flexors aren’t used as prominently as they are in the higher hip extension values found in upright running. The piston like action of early accel has more concentric dominant hip flexion because of this. If athletes only do accel based work you tend to see restricted hip extension and limited thigh separation which results in shorter stride lengths and athletes that can’t open up.

- 2.Quadzilla and Quad Lock- This point relates to the first, but has a much cooler heading. Acceleration is a more quad dominant sprint action. Accel dominant athletes lacking complementary running tend to function quad heavy aka “quadzilla” which may not be ideal for their sport. They can do all the posterior chain dominant weight room work in the world, but if they never use it in relevant scenarios at relevant speeds they are limiting performance. If you’ve ever seen a running back burst through the line and then at 15-20 yards look like they are tight and stuck in the mud that’s some “quad lock” (redheaded cousin of booty lock that may be more aptly titled “quad block”).

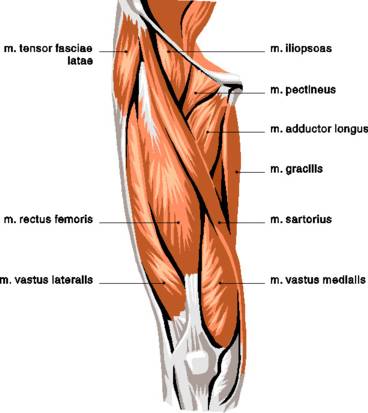

- 3.Tissue Issues- As described above acceleration overloads the quads and the hip flexor complex more than upright running. I’ve learned from working on my athletes (and working with soft tissue professionals much more skilled than I) that appreciable accel volumes often produce high tone and localized areas of restriction in the quads and hip flexor complex. The quads have much more variety of fiber type than the hamstrings (Quads are anti-gravity muscles often functioning at lower loads. The hamstrings are more predominantly fast twitch in nature). With this varying fiber type I’ve see more localized areas of disturbed tone and myofascial tightness. Foam rolling the quads does seem to help (good manual therapy is awesome). However, chronic loaders that never visit other realms to exercise tissue elasticity and freedom often end up with concrete quads. The out of whack tonus and extensibility here often shows up in points 1 and 2 and is a feeder of points 4, 5, and 6.

- 4.Tissue Issues Part 2 and Hip Flexor Dysfunction- In the acceleration action the psoas receives less elastic load to lengthen. Without complementary upright work athletes tend to end up short and sometimes dysfunctional here. Things you’ll see are a tight psoas and often folks that become restricted and sometimes dominant through the two joint hip flexors, notably Rectus and TFL. If the technique is poor or the accel action excessively overloaded (remember also that loaded sprints and hills retard hip extension even more) you’ll sometimes see lateral stepping which overloads the adductors. This abducted and usually externally rotated position also brings the adductors into play as too prominent a hip flexor.

- 5.Injuries from Insult- Take the first 4 problems via one-sided volume and multiply by time. It’s not a surprise you see hip flexor and pelvic floor issues in sports that go predominantly short (football, soccer, hockey… sports hernia anyone?). Additionally, acceleration is an anterior pelvic tilt based activity. Combine that with the more anterior chain dominant tissue recruitment inherent to the activity and too much accel tends to further anterior tilt (by contrast high quality upright speed is more of a posterior tilt activity). Unchecked, this anterior alignment shift often puts folks at risk for core/hip flexor dysfunction, back issues, and puts the posterior leg musculature at a mechanical risk. Lower crossed, gross extension pattern, call it what you like, but sometimes the sprint and run programming isn’t helping and is part of the blame. The tissue and alignment issues mentioned here, and in the earlier points above, often leave people hip flexor hamstrung. Frequently the hamstrings pay the price for compromised extension patterns.

- 6.Performance Problems- This is touched on in points one and two, but if all you work is one end of the spectrum you are going to end up unprepared. One, you don’t actually achieve what you are capable of on the acceleration end and two you certainly aren’t fit to fly if you do get upright. Field and Court sports are acceleration based, but many of these acceleration positions and initiations are much more upright than 3 point stances and crouch starts. Higher center of mass initiations are more hip dominant and have a higher frequency. To excel in these scenarios you better have at least touched on and hopefully trained and prepared in that realm.

Above I’ve outlined some of the problems I’ve seen with accel dominant programs for field and court sport athletes. In part 2 I’ll discuss running options to complement the needed acceleration work while avoiding the problems listed above.